Author / Cherry it up (Reposted from Douban)

Today let’s talk about the so-called “neutral” or “rational” stance when writing, reading and thinking.

Every time there’s a hot social topic, we often see official media reminding readers to be “rational”, but in fact they are using official discourse authority to suppress other information sources; in life, women are often labeled as “irrational” and automatically excluded from important conversations; feminist voices on social media are often dismissed by various voices emphasizing “objectivity and neutrality”, as if taking a stance is inherently wrong; in comment sections on Weibo, Douban or Zhihu, casually discussing phenomena or sharing thoughts often leads to being lectured about “seeing both sides” and “looking at issues dialectically”…

These “rational” voices occupy the moral high ground and seem impeccable at first glance, but they often make people feel uncomfortable. Why? - Because in these contexts, the so-called “neutrality”, “rationality”, and “seeing both sides” are accomplishing evil, suppressing voices that should be heard.

This problem is sometimes subtle and difficult to argue against in some cases, which is exactly why it needs to be laid out and discussed with everyone.

1. The Cost of Neutrality

What is "neutrality"? The dictionary explains it this way:

-

The state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict, disagreement, etc.; impartiality.

-

Absence of decided views, expression, or strong feeling.

In short, “neutrality” means neither supporting nor opposing, completely staying out of it. This stance can be typically seen in Switzerland’s permanent neutrality during World War II, neither getting involved nor helping.

Those familiar with TOEFL writing may know that a “neutral” stance is not very advantageous in TOEFL essays, as it gives grading teachers an impression of unclear position and weak viewpoints.* This observation certainly doesn’t mean “neutrality” can’t produce high-scoring essays, nor does it mean “neutrality” is necessarily a bad stance.

However, “neutrality” is indeed not the best stance when facing many discussion issues, sometimes it’s even a non-existent stance, or more seriously, it could be a hypocritical stance worse than prejudice.

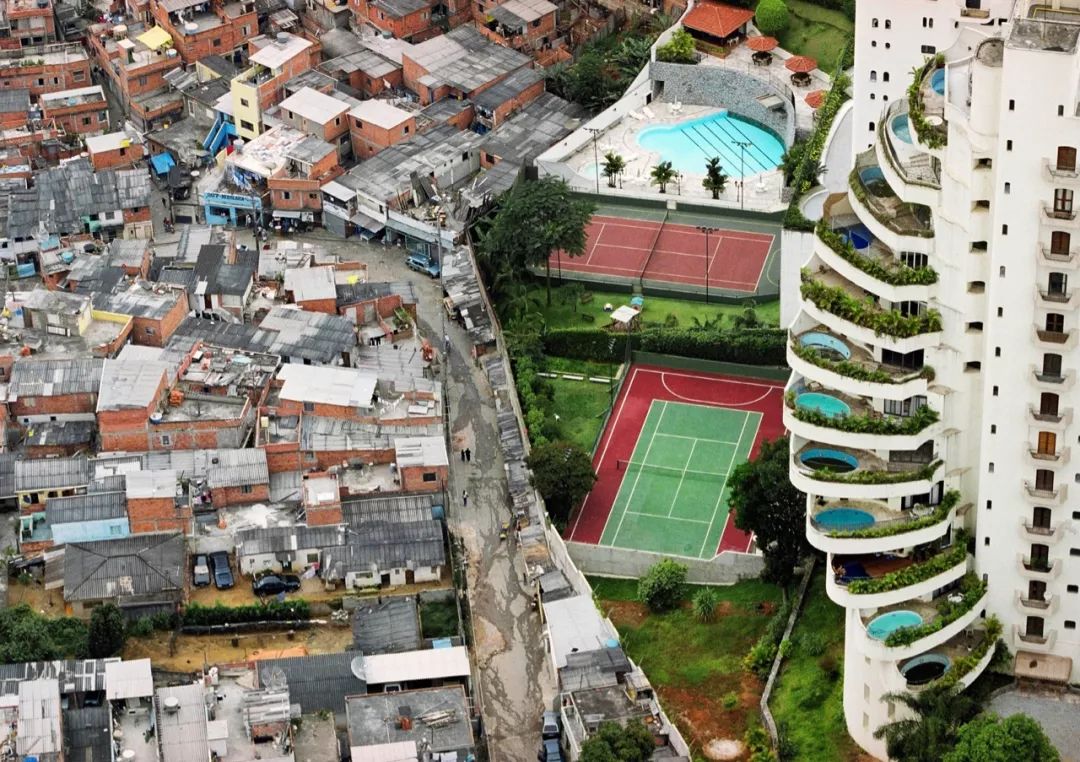

1.1 Being Able to Choose “Neutrality” Implies Privilege

Apart from the stance of giving equal criticism to both sides in TOEFL writing, in many contexts, “neutrality” is used as the opposite of “biased”. We often see angry feminists being attacked by supposedly “neutral” viewpoints, accusing them of being too radical. For these voices, I recommend here a very compelling article [1], which provides us a way to counter: if someone has the conditions to remain “calm” about injustice and choose to neither support nor oppose, it shows that they at least haven’t been oppressed by this injustice, meaning they are some kind of beneficiary.

It must be nice to never have to worry about earning 23 cents less per dollar than someone else, solely because you were born with different reproductive organs.

In such situations, if this person says they won’t help the disadvantaged side because they are “neutral”, they are condoning injustice and becoming an accomplice to the oppressor. The article quotes a famous saying from South African human rights theologian Desmond Tutu: “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

Switzerland during World War II is an example. In Nazi-controlled Europe, Switzerland as a neutral country not only refused to accept Jewish refugees but also seized their assets [2]. Though nominally a permanently neutral country, in reality, by not intervening or stopping atrocities to seek its own safety, it effectively sided with the oppressors. Switzerland’s post-war criticism by the international community for aiding evil, and government officials’ public apology to Holocaust victims [3], already well illustrates that there is no innocent “neutrality”.

1.2 Not Using Power Is Also an Abuse of Power

When I watched TV as a child, I always wondered why there was an “abstain” option during voting, until later I understood that “abstain” votes actually have the same power as other votes, and sometimes say even more. It turns out that choosing not to use power is also a way of using power.

Yo-Yo Ma said something at a graduation ceremony that left a deep impression on me: “To not use our power is to abuse it.”

Graduating from higher education institutions already puts you above many others in the social pyramid. In this situation, if graduates don’t use their knowledge, privileges (from diplomas or even school reputation) to change social injustices and help those without these privileges, they are melting into the oppressor’s side and becoming accomplices to injustice. This choice is a waste of power, which is why “sophisticated egoists” cannot stand on ethical grounds.

A “neutral” stance also cannot protect anyone from influence. Going back to the World War II example, America watched from across the shore at the start of the war, maintaining a “neutral” stance. In 1934, then Attorney General Charles Warren said “in time of peace, prepare for keeping out of war”. In his article, Warren pointed out that “neutrality” doesn’t mean being able to stand aside and stay aloof; on the contrary, to protect its “neutral” status, America would have to negotiate with belligerent countries and give up many original foreign trade powers [4].

In short, when the nest falls, no eggs stay intact. Being “neutral” by relying on one’s advantageous position not only doesn’t go far morally but also brings a lot of internal friction in practical operation.

1.3 Middle Ground Is Not Equal to Neutrality

Some might ask at this point, does one have to take sides completely to be reasonable? Is it wrong that I simply disagree with both extreme views? - You’re not wrong, most debates take place on a spectrum, and it’s neither possible nor should everyone only have black and white choices.

However, having a stance and staying completely uninvolved are two different things. Here I want to criticize those who use the banner of “neutrality” to avoid discussion, or even suppress other braver voices. Even “neutrality” needs to be responsible for its stance. This so-called “responsibility” means being able to stand up for your point, bearing the corresponding obligation to defend your viewpoint.

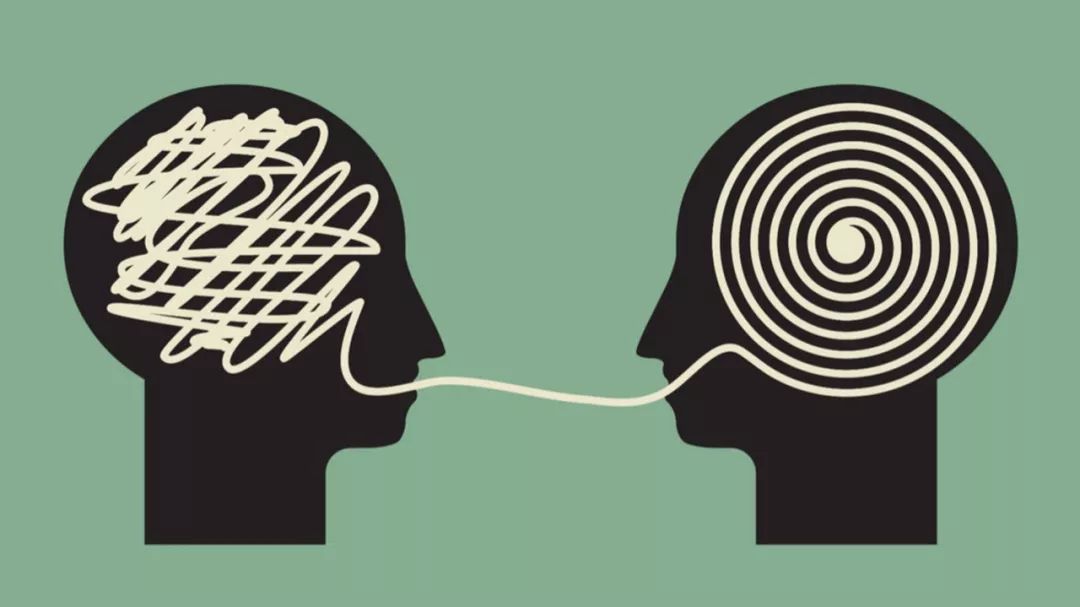

Conversely, humanities scholars have done so much work, from writing books to teaching classes, from public lectures to cooperating with NGOs, with the purpose of hoping more people can see the complexity of thinking and the multifaceted nature of society. Only when people can clearly explain their gray areas in clear language can communication between people be promoted and prejudices reduced.

Although I am skeptical of the “neutrality” discussed above, I think middle ground is a very worthy concept to promote. There’s a phrase in English called “meet in the middle ground” that I find particularly apt: We can’t force people to immediately abandon their standpoint, but if we can ask them to temporarily take a small step out to reach a middle ground, to listen to voices from other perspectives, to look at others’ positions, that’s already great progress. Even if participants’ positions haven’t changed currently, at least in such repeated meetings, they might start to understand why some people disagree with them, why they have their current position. Establishing such middle ground is the beginning of avoiding closed-mindedness, and avoiding closed-mindedness is the foundation for preventing extreme thinking.

In summary, my criticism of “neutrality” is not to push everyone to extremes. When facing discussions, “neutrality” as a stance often carries a negative avoidant attitude, while an impartial stance is first able to actively speak up and face challenges head-on. Secondly, the function of an impartial mediator is not to avoid problems/smooth things over, but to bring both sides of the argument to middle ground, providing effective communication channels and safe spaces.

Before ending this discussion, finally I recommend a YouTube channel Jubilee, they’ve done a series of middle ground videos, bringing people from both extremes into a room to discuss their topics. In these videos we’ll see some people refuse to listen to others’ viewpoints, and also see some people try to understand and empathize with others’ positions. Regardless of how each individual reacts, this kind of program is very educational for both participants and viewers. This channel also does a series called spectrum, which is also very interesting and helpful for changing social prejudices, highly recommended.

2. The Myth of Objectivity

After discussing “neutrality”, let’s talk about the stickier issues of “objectivity” and “rationality”.

First, we need to clarify that “objectivity” and “rationality” are two different conceptual categories.

In modern Chinese, “objectivity” generally corresponds to “objectivity” in English, and is the opposite of “subjectivity”. Its meaning can roughly be traced back to materialism, or (in a more colloquial context) localized Marxist materialism. Although philosophically “objectivity” refers to what exists independently of individual subjective will (subjectivity), when used in daily life/media discourse, “objectivity” often comes closer to meaning “neutrality”, implying that certain information has not been influenced by personal factors.

“Rationality” generally corresponds to “reason” or “rationality” in English, with meanings largely inherited from the rational tradition following the Enlightenment.

Regarding the semantic scope of these two terms, this section first discusses the limitations of “objectivity” and the problems it derives. Reflection on the “rational” tradition will be analyzed in the next section.

2.1 Does Absolute “Objectivity” Really Exist?

Discussion about objectivity can be traced back to Plato’s time, and has consistently been one of the classic topics frequently discussed in modern Western philosophy. To avoid getting lost in too deep philosophical exploration and losing the purpose of this article (we are discussing how to handle and receive information in daily life, how to avoid logical confusion in writing), I’ll start here with an easier to understand TED video: The Objectivity Illusion by Lee Ross. (https://youtu.be/mCBRB985bjo)

In the lecture, psychologist Lee Ross quoted Einstein’s famous saying: “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.” In other words, what we believe to be real is actually a product of mind work. Furthermore, we often label something as “real” through its consistency, and if people around us also acknowledge this consistency, then the “reality” of this thing gains recognition, otherwise it will cause controversy.

Ross then points out that while this definition of “reality” might not encounter major problems in the material world, it often encounters problems when discussing complex social issues. To this, he lists three “illusions of objectivity” and their consequences:

-

People believe their cognition (as well as human beliefs, feelings, preferences, tastes, values, etc.) is real, therefore other rational people will also recognize it;

-

Optimism about one’s own cognition makes us believe that convincing those who don’t accept our cognition is easy;

-

For those who cannot be convinced by us, or who don’t agree with our cognition, we tend to form negative evaluations (such as thinking they are irrational, unreasonable, blinded by prejudice).

These three points are actually easy to understand in principle, but the difficulty is: when we are in the midst of discussion, and have a strong sense of identification with our own position, how do we avoid falling into this objectivity illusion?

The key to solving the “objectivity illusion” lies in C, that those who don’t accept our cognition should not be labeled negatively—what Ross didn’t mention in the video is that more hidden yet more worthy of vigilance than negative labels is the elite position, a kind of condescending belittlement, believing that those who don’t agree with our cognition are uncultured, of low quality, ignorant, and need to be educated by us to change.

This attitude on one hand creates resistance from others, and on the other hand forms a closed mindset on our side, rejecting information from other aspects. As mentioned earlier, sharing information and exchanging viewpoints are beneficial for forming middle ground, but it should not be placed in an unbalanced power discourse context.

In the internet age, many discussions end up becoming flame wars, which is an inevitable phenomenon caused by the cyborg nature of the internet, but this doesn’t prevent some corners of the internet from becoming platforms for dialogue between both sides of an argument. If we truly hope to establish a dialogue, then we shouldn’t directly attack the other side with “how can you still… in 2012”, but rather should start a discussion, “Where does your information come from?” “The information I’ve collected reveals more/different content, what do you think?” “Why do you trust this information source but not that one?” “Let me explain why I think this information source is more reliable”…

In short, the above questioning of “objectivity” reminds us that when someone/media uses “objective truth” to tout themselves, what they’re conveying is not just “I haven’t added personal bias, so you can completely trust me”, but rather “I believe I haven’t been interfered with by other factions, here is my narrative and interpretation of this matter, and I believe I’m right, so you should believe me.” Therefore, this kind of “objective” rhetoric doesn’t mean the person/media itself is transparent and colorless. On the contrary, it is precisely this touting of “objectivity” that more easily leads people to endow the information source with a kind of authority, thus ignoring other different information sources.

In an article titled “On the Question of Objectivity”, philosopher Alfred H. Jones made a very apt analogy when introducing new realism: cutting a piece from a cloth, the distinction between reality and appearance is like the cut piece and the remaining cloth; the cut part that’s useful is called “reality”; the remaining useless part is called “appearance”.

Therefore, the profound problem brought by information explosion is not rumors or so-called fake news, but rather that trimmed partial information is often taken as “reality” to suppress the remaining information. In some societies where media and power discourse are closely linked, when authoritative discourse uses value judgments like “objectivity” and “rationality” to establish authority for itself, it actually pushes other information sources and other voices outside public view, readers should be particularly mindful of this phenomenon.

And when we criticize a viewpoint in writing, using whether it’s “objective” as a measuring standard has limited usefulness; rather than discussing whether a viewpoint is “independent of subjective emotions”, it’s better to point out the assumptions behind it and the premises for its arguments to stand, then analyze them.

Regarding philosophical discussions of objectivity, we can also distinguish between perception and conception. This is a pair of concepts commonly used in psychology/philosophy. Simply put, the former refers to our body’s perception and feeling of things; the latter shares the same root as “concept”, referring to the formation of concepts about something in our consciousness. After clarifying these two perceptual abilities, we can talk more accurately about “reality”.

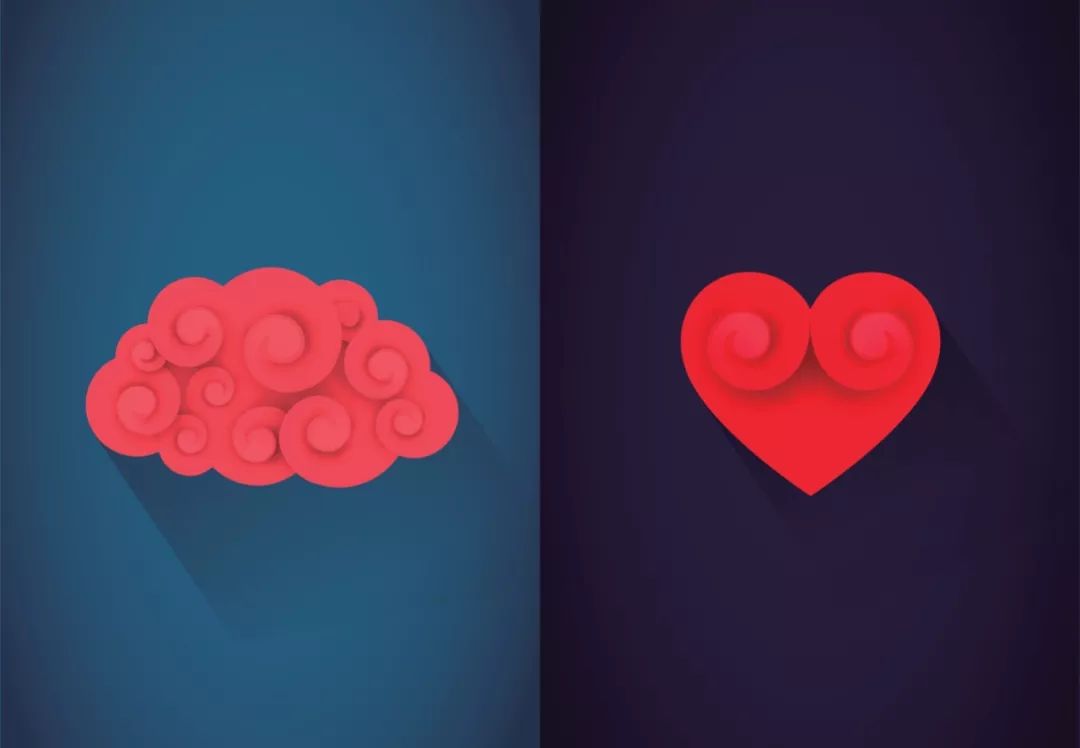

2.2 The Myth of “Emotion”

After discussing the limitations of the concept of “objectivity” itself, let’s look at how our society’s prejudice against “emotion” and treating “calmness” as a virtue have both influenced discussions in society.

Myth 1. Emotion is Shameful

Social shame comes from a systematic fear.

It should be well known that the government fears public emotion, and we ordinary people often feel the pressure brought by the social stigma of emotion: crying in public is embarrassing, arguing loudly is awkward, people with large emotional fluctuations are annoying, therefore, people of high quality should conceal their emotions well, not letting them show to others. Although I do believe emotional management is a very important skill, here I want to discuss a more fundamental question: why are we afraid of emotions?

The simplest answer is: because emotions are contagious.

For authorities, the danger of this contagiousness lies in that it can be expressed as public demonstration, thus threatening their position and authority.

For individuals, the danger of this contagiousness lies in that others’ emotions can affect our bodies—even self-generated emotions are stigmatized, because emotions are highly infectious and sometimes can make people lose the ability to think. Although scientific research shows that only a very small part of our consciousness is under our own control, that small part of control makes us mistakenly believe we are in control of ourselves, and when emotions strike, people fall into a fear of losing control. This fear comes not so much from the physiological reactions brought by emotions, but rather from the panic when the illusion of being in control is punctured.

But are emotions really shameful? This question shouldn’t need much explanation, emotions as a physiological phenomenon naturally have nothing shameful about them. According to research by a neuroscientist, it usually takes only 90 seconds for emotions to go from being triggered to resolving in the body, and subsequent emotional reactions are driven by thinking patterns. So people don’t need to feel ashamed for having emotions, and our attitude towards emotions should focus on the level of subsequent thinking patterns.

As psychologist Brett Ford mentioned in an article, viewing emotions as positive, natural, and beneficial is better for our physical and mental health; accepting emotions and letting them express naturally can reduce psychological burden and allow emotional fluctuations to be resolved more smoothly. Therefore, the expression of emotions itself should not be stigmatized.

Furthermore, the information conveyed by emotions is different from what “rationality” can express; that is, a line in a newspaper saying “Last night military conflict occurred in southern Syria, causing 203 civilian deaths or serious injuries” points to human rational thinking, while the crying of a child who survived the attack points to human empathy. Believing the latter is less important than the former is a simplified, one-sided understanding of human nature.

Myth 2. Emotion Necessarily Means Bias, While Calmness Means Impartiality

Returning to the issue of public topics and emotions. We often see such criticism in mainstream media: “stirring up emotions”, “carrying personal color”; mainstream discourse also often attaches “emotional” as a negative quality to certain groups (such as students, women), while “calmness” and “steadiness” are often praised as virtues. The logic behind this is that expressing emotion means abandoning rationality, thus becoming synonymous with being out of control and crazy.

Temporarily setting aside the limitations of “rationality” and “control” themselves, the harm caused by the values established by this logic is that the cries and accusations of those who have suffered injustice can easily be silenced by well-dressed “calm” authorities, and any story once labeled as “emotional” directly loses all value.

But at the same time, we also see that on social media, emotion is a very powerful currency for spreading information. The “public outrage” on Weibo is an important force in solving many social problems. It is precisely because emotions have infectiousness and can arouse people’s empathy that they have particularly high transmissibility, allowing some unjust things to get attention and false information to be quickly detected. Therefore, in many cases, “emotion” not only doesn’t mean bias, but rather means questioning and challenging a problem.

Besides this, in unjust social relationships, the agency of the oppressed is relatively limited, which in the communication process manifests as the oppressors having the right to use and interpret discourse, while the oppressed are in a state of speechlessness, unable to accurately narrate the injustice they have suffered.

At such times, emotions that transcend rational discourse become a breakthrough point that the latter can appeal to. Transcending established power discourse, using living cries and shouts to awaken others’ humanity, behind this is not just “sensationalism” done intentionally, but rather a challenge and deconstruction of established discourse. When dealing with structural social oppression (such as gender inequality), the expression of emotions and the creation of discourse need to go hand in hand, only when the weak create their own discourse to challenge the existing unjust discourse system can power structures be changed.

Author’s note: At this point, interested readers can read the short article “The Beggar” in Lu Xun’s Wild Grass collection. Besides this article, Lu Xun mentioned beggars multiple times in his various articles, always emphasizing that they are disliked because they are “not sad”, instead giving onlookers a sense of superiority of “I but dwell above the alms-giver”. The subtle psychology in this is worth pondering: the beggar’s “begging” is a kind of demand for emotion, while “rational” people usually carry a certain vigilance towards their own emotions, therefore, direct demands actually cause reverse psychology, “seeing through” the demander’s intentions instead becomes an opportunity to feel good. But is the beggar’s “not being sad” purely scamming? Not necessarily.

If we try to understand the story of Xianglin Sao using power discourse theory, it’s actually very clear: beggars themselves may really have unfortunate stories, but besides these stories, they have no subject that can explain and question the source of misfortune, and even less status to make their voices taken seriously, all they can do is repeatedly output their emotions, until these stories in turn devour them, becoming their very existence, until this repeated telling numbs others and numbs themselves, finally these unfortunate people become the embodiment of their own misfortune.

Seeing this clearly, when facing such emotional demands, perhaps we can think a little before feeling good about what kind of power mechanism is behind the misfortune, whether we can do something.

3. Reflection on Enlightenment Rationality

Regarding “rationality”, besides the elitist tendencies and the problem of concealing injustice under the banner of “rational neutrality” already pointed out in the previous text, there is more theoretical criticism. In the book “Three Critics of the Enlightenment”, Isaiah Berlin discussed three philosophers’ criticism of the Enlightenment movement. In analyzing Hamann, he particularly mentioned this philosopher’s reflection and criticism of the concept of “scientific rationality” and the values it evoked, which can provide us with ideas for discussing “rationality”.

Berlin points out that the rationalism of the Enlightenment has three basic theories:

-

Faith in reason, that is, believing in logical laws, and believing that laws can be tested and verified (demonstration and verification);

-

Belief in the existence of human nature and universal human pursuits;

-

Belief that human nature can be fully realized through reason, that is: through analysis and experiments by critical intellect, and a single theoretical system, all problems can be answered.

Obviously, this rationalism has a problem: believing that rational laws should apply everywhere and in every situation. This criticism is particularly worthy of attention in the humanities field, facing a postmodern era, many problems we encounter are inherently discursive, requiring repeated understanding and narration from many different paths, and the final result is rarely a clean unit, but rather an intricate and complex web.

Believing that “reason” can completely replace faith, believing that everything can be explained by laws and rules, this thinking makes people avoid many contingent factors and randomness in human society/nature. This avoidance of arbitrariness can also lead people to fall into closed thinking, believing that anything beyond rational understanding must be problematic, or believing that what cannot be completely rationally inducted is meaningless. At the same time, since the rationalization process is a theorization process, it often accompanies abstraction and categorization, and categorization means simplifying a spectrum into several segments, leaving those problems or people between categories at a loss, typical examples can be seen in today’s gender politics discussions.

Regarding Hamann’s criticism of the Enlightenment, there are many very interesting philosophical discussions, but due to space limitations I won’t expand on them here, readers interested in this part can further read Berlin’s other anti-Enlightenment articles, as well as works on postmodernism and post-structuralism.

In short, the purpose of this blog is not to deny the necessity of these concepts and the importance of independent thinking, but hopes through listing possible problems and noteworthy points behind these concepts to provide some ideas for everyone when establishing writing positions. After saying so much, what I want to say in the end is actually one sentence: Impartial discussions often beat around the bush, don’t be afraid of prejudices and emotions, sincerity and seriousness are sometimes more useful; knowing the boundaries of reason and the existence and significance of emotions, then using them well, this is how to advance the deepening of viewpoints.

Put positions in context for analysis and understanding, understand that prejudice and sincerity are equally precious and inseparable. Berlin on Hamann is a good example: His attacks upon it are more uncompromising, and in some respect sharper and more revealing of its shortcomings, than those of later critics. He is deeply biased, prejudiced, one-sided; profoundly sincere, serious, original; and the true founder of a polemical anti-rationalist tradition which in the course of time has done much, for good and (mostly) ill, to shape the thought and art and feeling of the West. (Berlin 318)

4. Conclusion

This blog has taken too long, I was thinking of splitting it into three articles, but for the completeness of the discussion, and to avoid falling into the tragedy of digging holes without filling them again, I still kept it in this long article. I originally wanted to discuss “division into two” and “xx-characteristic dialectics” as well, but after writing these three sections found that most of the principles have already been discussed once, the only thing not mentioned is criticism and reflection of Hegelian dialectics, readers interested in this can research themselves, I’m not a philosophy blogger after all, so I won’t pretend to be an expert. As for nationalized dialectics, my basic attitude is the same as towards the so-called media “objective” position and “rational” voices discussed earlier, I’ll leave the specific analysis for everyone to think about themselves.

Finally, ending the whole article with a sentence I found in a fortune cookie last week:

A good argument ends not with victory, but progress.

The meaning of debate is not in winning, but in progress. /

-

[1] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/why-neutrality-is-just-as-harmful-as-prejudice_b_10546240

-

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/1997/01/26/weekinreview/the-not-so-neutrals-of-world-war-ii.html

-

[3] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/nazis/readings/sinister.html

-

[4] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1934-04-01/troubles-neutral