原始文章

五年前,我和我的大学好友 Dayv 坐在一起喝啤酒。 我在 Twitter 上滚动,看着人们对唐纳德特朗普最近的愤怒感到愤怒,我说 “你知道……十五年前,互联网是逃离现实世界的一种方式。 现在,现实世界是对互联网的逃避。” “Tweet that!”,Dayv 说,我也这麽做了。 那个平庸的观察成为我有史以来最受欢迎的推文,这句话现在已经在整个网络的内容工厂中无限发布。

Five years ago I was sitting around drinking a beer with my college buddy Dayv. I was scrolling through Twitter and watching people get mad at Donald Trump’s latest outrage, and I said “You know…fifteen years ago, the internet was an escape from the real world. Now the real world is an escape from the internet.” “Tweet that!”, Dayv said, so I did. That banal observation became my most popular tweet of all time, and the quote has now been posted ad infinitum on content mills all over the web.

为什麽如此平淡的观察会引起这麽多人的共鸣? 很容易理解为什麽互联网现在感觉像是我们需要逃离的地方。 智能手机将互联网物理连接到我们的人身上; 现在我们无论走到哪裡都带着互联网,它的彩色小图标总是在招手,告诉我们放弃我们正在与之交谈的人或我们正在做的事情并检查最新的帖子。 但更难记住的是,为什麽互联网曾是人们逃离现实世界的避风港。

Why did such a bland observation resonate with so many people? It’s easy to see why the internet now feels like a place we need to flee from. The smartphone physically attached the internet to our persons; now we take the internet wherever we go, and its little colored icons are always beckoning, telling us to abandon whoever we’re talking to or whatever we’re working on and check the latest posts. But what’s harder to remember is why the internet used to be an escape from the real world.

当我小时候第一次接触互联网时,我做的第一件事就是找到和我一样喜欢的人——科幻小说和电视节目、龙与地下城等等。 在早期,这就是你上网时所做的事情——你找到你的人,无论是在 Usenet 或 IRC 或网络论坛或 MUSHes 和 MUD 上。 在现实生活中,你不得不与一群惹你生气的人打交道——不喜欢你政治的同事、唠叨你找一份真正工作的父母、开着豪车的受欢迎的孩子。 互联网是你可以和其他傻子一起做傻子的地方,无论你是动漫迷还是自由主义者枪迷,还是孤独的 40 多岁的基督徒,还是仍然在壁橱裡的同性恋孩子。 社区是逃生口。

When I first got access to the internet as a kid, the very first thing I did was to find people who liked the same things I liked — science fiction novels and TV shows, Dungeons and Dragons, and so on. In the early days, that was what you did when you got online — you found your people, whether on Usenet or IRC or Web forums or MUSHes and MUDs. Real life was where you had to interact with a bunch of people who rubbed you the wrong way — the coworker who didn’t like your politics, the parents who nagged you to get a real job, the popular kids with their fancy cars. The internet was where you could just go be a dork with other dorks, whether you were an anime fan or a libertarian gun nut or a lonely Christian 40-something or a gay kid who was still in the closet. Community was the escape hatch.

然后在 2010 年代,互联网发生了变化。 不仅仅是智能手机,儘管它确实使它成为可能。 发生变化的是,互联网互动越来越多地开始围绕少数极其集中的社交媒体平台展开:Facebook、Twitter,以及后来的 Instagram。

Then in the 2010s, the internet changed. It wasn’t just the smartphone, though that did enable it. What changed is that internet interaction increasingly started to revolve around a small number of extremely centralized social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, and later Instagram.

从商业角度来看,这种集中化是早期互联网的自然延伸——人们之间的联繫越来越紧密,所以让他们联繫得更多。 当每个人的主页都可以成为他们的 Facebook 页面时,为什麽每个人都要做自己的网站? 当您可以直接在 Twitter 上与任何人交谈时,为什麽还要尝试在 IRC 聊天室中追踪人们? 让世界上的每个人都通过单一网络联繫是我们对电话系统所做的,而且每个人都知道网络的价值与用户数量的平方成正比。 因此,将整个世界的社交互动集中在两个或三个平台上将印出大量金钱,同时也会创造一个更快乐、联繫更紧密的世界。

From a business perspective, this centralization was a natural extension of the early internet — people were getting more connected, so just connect them even more. Why have everyone make their own websites when everyone’s homepage could just be their Facebook page? Why try to track people down in IRC chat rooms when you could just talk to anyone directly on Twitter? Putting everyone in the world in touch through a single network is what we did with the phone system, and everyone knows that the value of a network scales as the square of the number of users. So centralizing the whole world’s social interaction on two or three platforms would print loads of money while also making for a happier, more connected world.

它肯定是前者。 Facebook 成为了一个无坚不摧的企业巨头,而 Twitter 儘管管理不善是出了名的,但仍设法保持盈利并免受竞争。 但几乎在 2010 年代高度集中之后,我开始注意到我所熟悉和喜爱的互联网出了点问题。

It certainly did the former. Facebook became an all-conquering corporate behemoth, and Twitter managed to stay profitable and secure from competition in spite of being notoriously poorly managed. But almost immediately after the great centralization of the 2010s, I started noticing that something was wrong with the internet I had come to know and love.

它始于 Facebook 提要。 在旧互联网上,您可以在每个论坛或聊天室中展示自己不同的一面; 但是在你的 Facebook 动态中,你必须是你认识的每个人的同一个人。 当 2010 年代中期爆发社会动盪时,情况变得更糟了——你不得不看着你的自由派朋友和保守派朋友在你或他们的帖子的评论中做出反应。 那些评论破坏了友谊甚至家庭纽带。

It started with the Facebook feed. On the old internet, you could show a different side of yourself in every forum or chat room; but on your Facebook feed, you had to be the same person to everyone you knew. When social unrest broke out in the mid-2010s this got even worse — you had to watch your liberal friends and your conservative friends go at it in the comments of your posts, or theirs. Friendships and even family bonds were destroyed in those comments.

起初 Twitter 似乎没有 Facebook feed 那麽糟糕,因为如果你不想的话,你不必透露你的真实身份。 但 Twitter 将全世界的每个人聚集在一起的方式要极端得多。 你的家人和朋友可能会在 Facebook 上打架,但至少你不必被随机匿名纳粹分子或共产主义者或对视频游戏新闻发狂的怪人的愤怒评论淹没。

At first Twitter seemed less bad than the Facebook feed, since you didn’t have to reveal your real identity if you didn’t want to. But Twitter was far more extreme in the way it threw everyone in the whole world together. Your family and friends might fight on Facebook, but at least you didn’t have to get deluged with angry comments from random anonymous Nazis or communists or weirdos mad about video game journalism.

2010 年代早期 Twitter 的定义是关于毒性和骚扰与早期互联网言论自由理想的斗争。 但在 2016 年之后,这些斗争不再重要,因为平台上的每个人都简单地採用了极端主义巨魔开创的相同的毒性和骚扰模式。 到 2019 年,你可能会被愤怒的图书管理员、週六夜现场的粉丝或历史教授包围。 对付愤怒的暴民的唯一防御,就是让你自己成为愤怒暴民。 Twitter 感觉就像一座监狱,在监狱裡你需要一群帮派才能生存。

The early 2010s on Twitter were defined by fights over toxicity and harassment versus early-internet ideals of free speech. But after 2016 those fights no longer mattered, because everyone on the platform simply adopted the same patterns of toxicity and harassment that the extremist trolls had pioneered. By 2019 you could get mobbed by angry librarians, or Saturday Night Live fans, or history professors. The only defense against an angry mob was to get your own angry mob. Twitter felt like a prison, and in prison you need a gang to survive.

为什麽在过去几十年的去中心化互联网上没有发生这种情况,而在中心化互联网上却发生了这种情况? 事实上,周围总是有纳粹分子、共产主义者,以及所有其他有毒的巨魔和疯子。 但他们只是一个烦恼,因为如果一个社区不喜欢这些人,版主就会禁止他们。 即使是普通人也被禁止进入他们的论坛

Why did this happen to the centralized internet when it hadn’t happened to the decentralized internet of previous decades? In fact, there were always Nazis around, and communists, and all the other toxic trolls and crazies. But they were only ever an annoyance, because if a community didn’t like those people, the moderators would just ban them. Even normal people got banned from forums where their personalities didn’t fit; even I got banned once or twice. It happened. You moved on and you found someone else to talk to.

社区审核有效。 这是早期互联网的压倒性教训。 它之所以有效,是因为它反映了现实生活中的社会互动,社会群体排斥那些不合群的人。它之所以有效,是因为它将监管互联网的任务分配给了大量志愿者,这些志愿者提供免费的维护工作 论坛很有趣,因为对他们来说,维护社区是一项热爱的工作。 它之所以有效,是因为如果你不喜欢你所在的论坛——如果模组过于苛刻,或者如果它们过于宽松并且社区已被巨魔接管——你只需走开并找到另一个 论坛。 用伟大的 Albert O. Hirschman 的话来说,您始终可以选择使用“退出”。

Community moderation works. This was the overwhelming lesson of the early internet. It works because it mirrors the social interaction of real life, where social groups exclude people who don’t fit in. And it works because it distributes the task of policing the internet to a vast number of volunteers, who provide the free labor of keeping forums fun, because to them maintaining a community is a labor of love. And it works because if you don’t like the forum you’re in — if the mods are being too harsh, or if they’re being too lenient and the community has been taken over by trolls — you just walk away and find another forum. In the words of the great Albert O. Hirschman, you always have the option to use “exit”.

然而,从推特上看,似乎没有出口。 你会去哪裡? 如果您是一名记者,那麽 Twitter 就是所有最新消息的来源。 如果你是一个不同意记者的普通人,想直接当着他们的面大喊大叫,那麽 Twitter 是你唯一可以做到的地方。 如果你想把它混入永无止境的政治和文化事务中,推特是你可以获得最多观众的地方,并且感觉你的影响力最大。 複製 Twitter 很容易——右翼分子尝试了几次,用 Gab、Parler 和 Truth Social——但感觉原始版本的网络效应无法克服。 所以你日復一日地回去,忍受灌篮暴徒的毒性,再次投入战斗。

From Twitter, however, there seemed to be no exit. Where would you go? If you were a journalist, Twitter was the source for all the most up-to-the-minute news. If you were a regular person who disagreed with journalists and wanted to yell directly in their faces, Twitter was the only place you could do that. If you wanted to mix it up in the neverending scrum of political and cultural affairs, Twitter was where you could get the largest audience for that, and feel like you had the largest impact. It was easy to clone Twitter — right-wingers tried several times, with Gab, Parler, and Truth Social — but it felt like the network effect of the original just couldn’t be overcome. So you went back day after day, to endure the toxicity of the dunk-mobs and throw yourself once more into the fight.

而在企业方面运营 Twitter 的人根本无意改变这一点。 他们可能已经就“言论自由”谈了一个很好的游戏——每个人都这样——但他们真正想要的是继续赚钱。 他们修补了平台的边缘,但从未触及他们的杀手级功能,即引用推文,Twitter 的产品负责人称之为“灌篮机制”。 因为扣篮是商业模式——如果你不相信我,你可以查看许多研究论文,这些论文表明恶意和愤怒推动了 Twitter 的参与。

And the people who ran Twitter on the corporate side had no intention of changing this at all. They may have talked a good game about “free speech” — everyone does — but what they really wanted was to keep making money. They tinkered at the edges of the platform, but never touched their killer feature, the quote-tweet, which Twitter’s head of product called “the dunk mechanism.” Because dunks were the business model — if you don’t believe me, you can check out the many research papers showing that toxicity and outrage drive Twitter engagement.

🚨This is the trap that social media, and by extension all of us, are in:

— Ethan Mollick (@emollick) November 20, 2022

📈Toxicity drives use. Lowering toxicity drops ad sales (if you are ad supported) & engagement (even if you are not)

📉Toxicity spreads like a disease. It turns regular users toxic & makes networks awful pic.twitter.com/NeqlZ4G05H

公司倒霉、无能的管理层找不到更好的模式,所以他们固执地坚持现有的模式。 他们坚决抵制任何带有社区节制意味的行为——从话题视图中删除被屏蔽的用户评论,允许用户从他们的话题中删除回复,等等。

The company’s hapless, incompetent management couldn’t figure out any better model, so they clung doggedly to what they had. They steadfastly resisted anything that would smack of community moderation — dropping blocked users’ comments from thread view, allowing users to remove replies from their threads, etc.

夹在网络效应的轻松盈利和对毒性的日益增长的愤怒之间,大型社交媒体平台转向了中心化的节制。 毫不奇怪,这没有用。 这不仅对版主本身来说是一项不可能完成的任务,而且这意味着公司的管理层基本上需要採取编辑倾向。 这有效地破坏了社交媒体公司的形象。 而且由于 Twitter 的编辑倾向稍微偏左,这让保守派特别生气。 Facebook 意识到这项任务的不可能,最终决定将其 Feed 完全从新闻中移除; 推特当然做不到这一点。

Caught between the easy profitability of network effects and growing anger over toxicity, the big social media platforms turned to centralized moderation. Unsurprisingly, this didn’t work. Not only was it an impossible task for the moderators themselves, but it meant that the management of the company was basically required to take an editorial slant. That effectively wrecked the image of the social media companies. And because Twitter’s editorial slant leaned slightly left-of-center, this made conservatives especially mad. Facebook, realizing the impossibility of the task, finally just decided to move its feed away from news entirely; Twitter, of course, couldn’t do this.

随着这种情况持续存在,我开始注意到一种趋势。 人们正在将他们关于新闻、政治和公共事务的讨论从 Twitter 转移到更小的论坛——首先是 Twitter DM 组,然后是 WhatsApp、Signal 和 Discord。 他们仍然保留着自己的 Twitter 账户,并在公开场合发表了一些言论,但他们的诚实意见越来越多地在一群可信赖的朋友和意识形态一致的熟人(以及偶尔表现出在意识形态上足够宽容的经济学博主 被右翼和左翼团体接纳)。 慢慢地,人们似乎重新发现了旧互联网教给我们的真理——当你可以选择与谁交谈时,讨论会更有效。

As this situation persisted, I began to notice a trend. People were taking their discussions about news, politics, and public affairs off of Twitter and into much smaller forums — first to Twitter DM groups, then to WhatsApp, Signal, and Discord. They still maintained their Twitter accounts and said a few things in public, but their honest opinions more and more were said in the privacy of a trusted group of friends and ideologically aligned acquaintances (and the occasional economics blogger who comes off as ideologically tolerant enough to be admitted to both right-wing and left-wing groups). Slowly, people seemed to be rediscovering the truth that the old internet had taught us — that discussions work better when you can pick and choose who you’re talking to.

然后 Elon Musk 出现了。

马斯克是一颗流星坠入僵化的 Twitter 恐龙世界,对其社区及其规范(如果还不是其基本功能)造成严重破坏。 如今,如果你上推特,你会发现它完全被马斯克的最新举动所吸引——今天,它任意禁止批评他的记者,昨天,它禁止一个跟踪他的私人飞机的账户。 明天会是另外一回事。

Then Elon Musk came along.

Musk is a meteor crashing into the ossified dinosaur-world of Twitter, wreaking havoc on its community and its norms (if not yet its basic functionality). Nowadays if you go on Twitter, you’ll find it absolutely absorbed by Musk’s latest move — today, it’s arbitrarily banning journalists who criticized him, yesterday it was banning an account that tracked his private jet. Tomorrow it will be something else.

马斯克的右倾中心化节制是否足以导致让 Twitter 享有主流媒体“任务台”美誉的普遍左倾记者的大量外流,或导致广告商放弃该平台,还有待观察 更普遍地转移到替代站点。 如果一般核心用户确实决定离开,预计该平台会突然衰落。

It remains to be seen whether Musk’s right-leaning centralized moderation will be enough to cause an exodus of the generally left-leaning journalists who give Twitter its reputation as the mainstream media’s “assignment desk”, or cause advertisers to abandon the platform, or result in a more general move to alternative sites. If core users in general do decide to leave, expect the platform to decline pretty abruptly.

但有趣的是,即使是那些确实期待这种外流的人似乎也不相信会有另一个单一的、统一的平台来取代 Twitter。 原始版本的外观和功能很容易複製,但似乎没有人认为每个人都会转向新的 Twitter; 每个人似乎都认为,如果 Twitter 确实衰落,那麽未来将是支离破碎的。

But what’s interesting is that even the people who do expect this sort of exodus don’t seem to believe that there will be another single, unified platform that just replaces Twitter. The look and functionality of the original is simple to replicate, but no one seems to think that everyone will just move to New Twitter; everyone seems to expect that if and when Twitter does decline, the future is fragmented.

因为也许,只是也许,我们已经吸取了教训。 也许我们已经意识到互联网作为一个碎片化的东西会更好地工作。

Because maybe, just maybe, we’ve learned our lesson. Maybe we’ve realized that the internet simply works better as a fragmented thing.

正如 Jack Dorsey 所写,集中式社交媒体是全球人类集体意识的一次盛大实验。 这是一座现代的巴别塔,是新世纪福音战士的人类工具项目。 是的,这是让一些人变得富有的一种方式,但它也是一个团结人类的实验。 或许如果我们都可以聚在一个房间裡互相交谈,如果我们可以摆脱我们的迴声室和过滤泡,我们最终会达成一致,而充满战争、仇恨和误解的旧世界就会融为一体记忆。

Centralized social media, as Jack Dorsey wrote, was a grand experiment in collective global human consciousness. It was a modern-day Tower of Babel, the Human Instrumentality project from Neon Genesis Evangelion. Yes it was a way to make some people rich, but it was also an experiment in uniting the human race. Perhaps if we could all just get in one room and talk to each other, if we could just get rid of our echo chambers and our filter bubbles, we would eventually reach agreement, and the old world of war and hate and misunderstanding would melt into memory.

那个实验失败了。 人类不想成为一个全球性的蜂群思维。 我们不是最终会达成一致的理性贝叶斯更新者; 当我们收到相同的信息时,它往往会使我们两极分化而不是团结我们。被不同意你的人尖叫和侮辱不会让你离开你的过滤泡泡——它会让你退回到你的泡泡裡,拒绝任何对你尖叫的人的想法。 没有人因为被扣篮而改变主意; 相反,他们都只是加倍努力扣篮。 Twitter 的仇恨和毒性有时感觉就像人类个性垂死的尖叫,被蜂群思维不断要求我们同意比我们进化到同意的人更多的人压死。

That experiment failed. Humanity does not want to be a global hive mind. We are not rational Bayesian updaters who will eventually reach agreement; when we receive the same information, it tends to polarize us rather than unite us. Getting screamed at and insulted by people who disagree with you doesn’t take you out of your filter bubble — it makes you retreat back inside your bubble and reject the ideas of whoever is screaming at you. No one ever changed their mind from being dunked on; instead they all just doubled down and dunked harder. The hatred and toxicity of Twitter at times felt like the dying screams of human individuality, being crushed to death by the hive mind’s constant demands for us to agree with more people than we ever evolved to agree with.

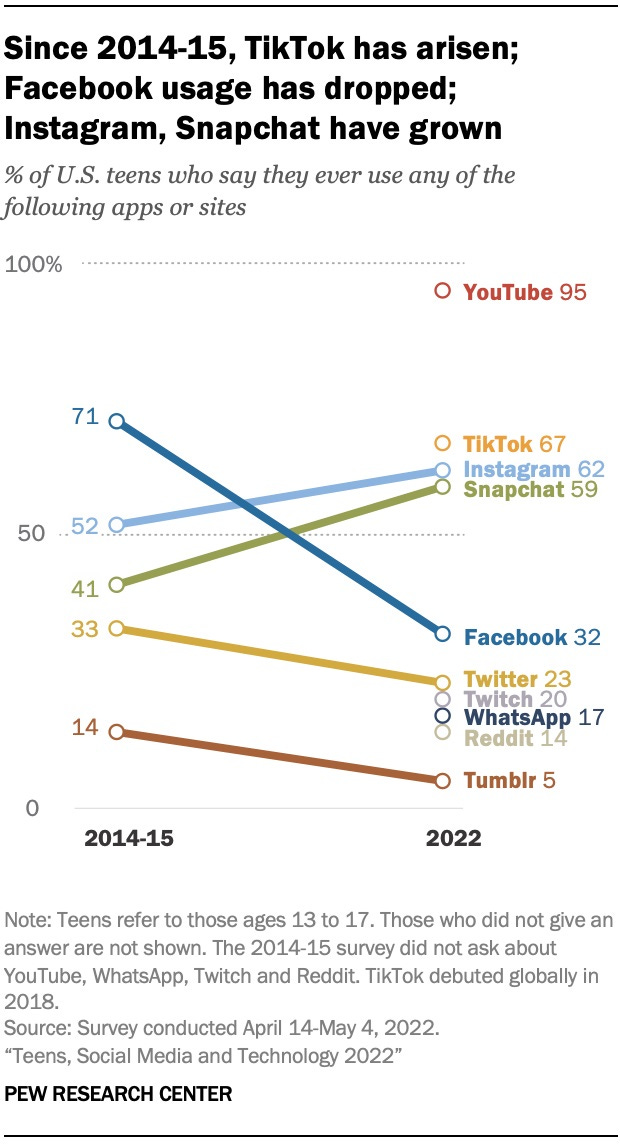

但人类的个性不会消亡。 相反,正在消亡的是集中式社交媒体。 社交媒体网络效应很强,但不是无限强。 最近的一项调查发现,只有三分之一的美国青少年使用 Facebook,低于五年前的 70% 以上。 甚至在马斯克接管之前,使用 Twitter 的青少年比例已经从 33% 下降到 23%。

But human individuality would not die. Instead it is centralized social media that is dying. Social media network effects are strong, but not infinitely strong. A recent survey found that only a third of U.S. teens use Facebook at all, down from over 70% just half a decade ago. And even before Musk’s takeover, the fraction of teens on Twitter had declined from 33% to 23%.

在集中式社交媒体的位置,我们看到了一些正在兴起的东西。 首先是 TikTok 和 YouTube; 儘管这些确实有一些评论功能,但总体而言它们更类似于电视、广播和传统的单向推送媒体,内容由算法驱动而不是用户共享。 其次,Snapchat 和 Instagram,它们更侧重于个人互动,而不是公共讨论。 虽然他们没有被包括在调查中,但我从轶事和整体使用趋势来看的一般感觉是聊天应用程序——WhatsApp、Signal、Discord 等——正变得越来越流行。

In place of centralized social media we see a few things rising. First, there’s TikTok and YouTube; although these do have some comment features, overall they’re far more similar to television, radio, and traditional one-way push media, with content driven by algorithms instead of user sharing. Second, Snapchat and Instagram, which are geared much more toward personal interactions and less toward public discussions. And though they weren’t included in the survey, my general sense from both anecdotes and overall usage trends is that chat apps — WhatsApp, Signal, Discord, etc. — are becoming more popular.

这些新兴的应用程序和平台的共同点是碎片化。 无论是有意识地自我分类到志同道合的群体或社区主持的群体,还是来自一群不同的人观看他们自己的算法策划的视频提要的自然碎片,这些应用程序都有一种根据他们想要的人分开的方法 与他们交谈以及他们想接触什麽。

What these rising apps and platforms all share is fragmentation. Whether it’s intentional self-sorting into like-minded or community-moderated groups, or the natural fragmentation that comes from a bunch of different people watching their own algorithmically curated video feeds, these apps all have a way of separating people based on who they want to talk to and what they want to be exposed to.

这就是我们恢復旧互联网的方式——不是以其原始形式,而是以其辉煌、支离破碎的本质。 人们称 Twitter 为不可或缺的公共空间,因为它是“城市广场”,但在现实世界中,并不只有一个城市广场,因为不只有一个城镇。 有许多。 当你可以退出时,互联网就可以工作——如果你不喜欢市长或当地文化,你可以搬到另一个城镇。 这并不意味着我们需要一个没有人与任何我们不同意的人交谈的世界——我们需要半透膜而不是厚牆。 一个分散的互联网,人们可以在其中尝试多个空间并从一个论坛移动到另一个论坛,非常适合提供这些膜。 社会上的分歧是进步所必需的,但当它以信任、亲和力和半隐私的纽带为媒介时,它是最具建设性的。 我们的界限总是会相互摩擦,但我们需要一些界限。

This is how we restore the old internet — not in its original form, but in its glorious, fragmented essence. People call Twitter an indispensable public space because it’s the “town square”, but in the real world there isn’t just one town square, because there isn’t just one town. There are many. And the internet works when you can exit — when you can move to a different town if you don’t like the mayor or the local culture. This doesn’t mean we need a world where nobody talks to anyone we disagree with — instead of thick walls, we need semipermeable membranes. And a fragmented internet, where people can try out multiple spaces and move from forum to forum, is perfect for providing those membranes. Disagreement in society is necessary for progress, but it’s most constructive when it’s mediated by bonds of trust and affinity and semi-privacy. Our boundaries will always rub up against each other, but we need some boundaries.

也许有一天人类会准备好成为一个集体意识。 但 2010 年代的实验表明,这一天不是今天。 让互联网再次成为一种逃避——一个你可以找到你的人并快乐的地方。 让我们再次学习说一千种不同的语言。 让巴别塔倒塌。

Perhaps someday the human race will be ready to become one collective consciousness. But the experiment of the 2010s shows that this day is not today. Let the internet once more be an escape — a place where you can find your people and be happy. Let us learn to speak a thousand different languages once again. Let the Tower of Babel fall.

巴别塔的意思

“巴别塔” 的意思是 “Babel Tower",通常指《创世纪》中故事中的巴别塔。这个故事讲述了人类在建造一座巨大的塔,以便能够到达天堂,然而上帝看见了人类的骄傲和野心,就把他们语言分裂成许多不同的语言,使得人类无法互相交流,最终停止了建塔的工作。巴别塔在像徵着人类的野心和自欺欺人的追求。

巴别塔故事

洪水之后,挪亚的儿子们生了很多孩子。地上的人越来越多,开始搬到不同的地方居住,跟耶和华之前吩咐的一样。

可是,地上有些人不听耶和华的话。他们说:「我们来建一座城吧,住在那裡,再建造一座塔,高得顶天,好让大家知道我们有多厉害!」

耶和华看到了,就很不高兴,要阻止他们。猜猜看,上帝会怎麽做呢?他让那些人一下子说起不同的语言,他们没法沟通,就不得不停工。后来,人们把那座城叫做巴别,意思就是「混乱」。人们的语言混乱之后,就分散到世界各地居住。他们在别的地方还是做坏事。